Research in Paris

Mozart's Mother 1777-78 Moliere and Mozart 19thrt century writers My memory lane of 1957 - au pair, the war in Algiers Living next to' Voltaire Thorkild Hansen 1947

|

Is there anything more

Parisian than Edith Piaff?

Paris

October 1st 2011

Charles de Gaulle Airport, a bit of an anthill, and

Europe’s second largest airport after Heathrow, revealed its worst sides in the

stifling heat. I swore at the useless wheels on my suitcase as well as the

heavy winter clothes, including trekking boots that I had brought... It was

cold in Copenhagen … How stupid was I!

The tiny iPod hardly weighed a thing and it is like

caviar to your ears, for a number of reasons:

The actor Klaus

Maria Brandauer’s recording of 365 ingenious letters to and from Mozart.

Granted, over the years, I have worked my way through Mozart’s letters more

than once, but his words keep providing me with new associations whenever I

hear them.

And the actor Senta

Berger’s recording of Martin Gecks ‘Mozart,

a Biography’. The former Bond-girl has developed into a great character

actor over the years. I so enjoy her lovely voice and her sensitive reading. I

make plenty of little notes in my notebook. As I am currently also in the

process of recording my own books, I can hardly find a better teacher than Senta Berger. Well, perhaps the Danish

actors Vigga Bro or Githa Nørby. I love the sound of elderly

ladies’ voices. The experience and passion … they are simply more daring.

I have also downloaded, as we say, lots of music onto

my little iPod. Mozart, of course, and much else, which I shall elaborate on in

some of the later blogs.

|

The copies of old copperplates from Paris in the 1770s weighed a lot more, but they were necessary if I wanted to retrace Mozart and his mother’s steps. I had also added a few travel books, not in the sense of how to get from A to B, because for that we can just access Google Earth, but more in terms of the memories of the people from the same era, not least the circle around Mozart.

What

connects Molière and Mozart?

We know that Fridolin

Weber, Constanze’s father gave Mozart his edition of Moliére’s collected works, a valuable gift at the time, and Don

Juan is after all one of Molière’s plays.

Whether it was Lorenzo da Ponte who came up with the

idea for Mozart’s opera … da Ponte had been a friend of the notorious seducer

Giacomo Gasanova in his youth … or whether it was Mozart who got interested in

the theme from reading Molière’s play, we do not know. But Mozart did spend much time thinking about and looking for

suitable themes for his operas, and he read numerous librettos, which he might

or might not have wanted to write the music for, so it is not all together

unlikely that he was inspired by Molière.

Molière, 1622-73 was baptized in the church

Saint-Eustache, from where Mozart’s mother was buried. Paris was only a small

town in those days.

The character ‘Don Giovanni’ dates all the way back to

the 1300s.

Pont Royal

However, the most important books I’d brought were Thorkild Hansen’s two-volume ‘A Studio

in Paris’- his journals from 1947-52.

Thorkild Hansen arrived in Paris in August 1947, on

the North Express, which arrived at Gare

du Nord at 4 pm each day. In one hand, he carried a midwifery bag with

underwear, and in the other, he carried a secondhand typewriter. He had a grant

that would last him six months and an agreement with the Danish Newspaper

Ekstrabladet about sending them articles, which was how he would make his

living there. He was twenty years old.

It was quite natural for me to be sent to do housework in Paris at the age of eighteen, granted as an au pair, while Thorkild Hansen, at the age of 20, was already a fully fledged writer, he had at least published his first book about Jacob Paludan. And if you want to read a gender difference into that, I certainly would not oppose.

Thorkild Hansen’s journal ‘A Studio in Paris’ opens with three quotes:

Paris - a fine place to be

young in, a necessary part of a man's education.

Hemmingway

Held den, som før hans Hu var tung

med rene øjne saa Paris.

Her blir den gamle Mester ung,

den unge Mester ser sig vis.

Sophus Claussen

I too arrived in Paris … sitting down all the way … on

the North Express, only it was ten years after Thorkild Hansen, and I was

eighteen years old. Paris had not changed much since the war, which still felt

very recent, and there was absolutely no money to be spent on modernizations.

Which was lucky for me, because if we disregard Baron Haussmann’s rigorous changes to streets and facades somewhere between 1853 and 1870, the remaining buildings looked pretty much as they would have, when Mozart and his mother, Maria Anna, arrived in 1777… on what was to be her last journey.

On the other hand, France had been at war since 1954

and this time the enemy was practically within - in the shape of the French

colony, Algiers. The rebel movement ALN, had taken the cloves off, as had

France, and that made an impact on everyday life in Paris. There were heavily

armed soldiers in front of all public buildings, and there were sacks with

decapitated Algerians. They had been on ALN’s ‘list of traitors’.

Not really an invitation to take a romantic stroll

along the Seine in the moonlight. On the contrary, I went absolutely nowhere

after dark, until I met Uschi (Ursula) in the Tuileries, where all au pairs as

well as the professional nounou’s (in

pale blue uniforms with bright white aprons) would take the children in their

care for walks

Ma Mère

We were both daughters of single mothers, which gave

us a sort of shared identity. Unmarried or divorced mothers were rare at that

time, and they were undoubtedly no good! My mother was divorced ... and rather

modern for her time. And she was a member of the Danish resistance. I have

outlined her in the novel ‘Somersault’, the second volume in my trilogy ‘The Labyrinth of Evil’. She was a

passionate woman who lived a life filled with sadness.

We quickly realised that we also shared the same sense

of humour; the most important foundation of any friendship. Furthermore, we

both loved reading and we were both eager to master the great French writers.

And when we partly succeeded in doing so, we practically drowned ourselves in

books. Books we borrowed from ‘my’ family’s extensive bookshelves. It was a

long time before Mac, iPod and iPad became our new reading devises. In fact, it

was even before ‘everyman’ had access to a television.

Uschi also worked for a family. However, she never

went beyond the children’s rooms and the kitchen, where she ate with the

youngest children. They were not allowed to sit at the dining table until they

were able to ‘eat properly, using a knife and a fork’!

Ushi attended French classes at Alliance Francaise,

something I was very envious of, but Madame’s husband, ‘Monsieur’, called

Alliance Francaise a ‘brothel’! There were always hordes of young men waiting

outside the entrance once school had finished, and it was his duty to look

after me while I was in his care. According to him.

I was sent to École Polytechnique instead, where I

attended evening classes with students who had not yet passed their A-levels,

or who needed to improve their grades in order to go to university. I only had

to attend the French lessons, which I was far from qualified for, but Monsieur

asked me to leave the office at the time of enrolment, and he was already

flirting away with the woman who had to stamp the papers in all the proper

places. He was a natural Don Juan, and his had his way.

It proved less successful for both me and my

professors, so I ended up leaving after only six months. I actually learnt more

from being at home with Madame.

Monsieur drove me back and forth in his really old

2CV. It was so ‘bouncy’ that if his chosen parking space was on the tiny side,

he would place me on the bonnet and tell me to bounce up and down, which

allowed him to park the shock absorber under the car parked in front! And then

it was just a question of getting out of there fast.

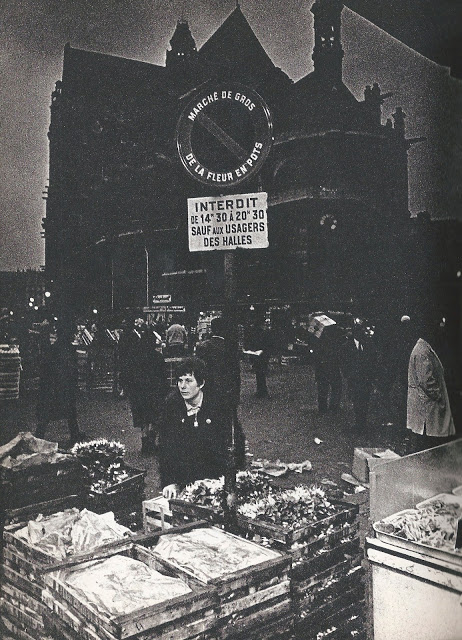

The weekly shopping in "Les Halles" was something special. More in a later blog including Saint Eustache and "Madam Mutter".

The weekly shopping in "Les Halles" was something special. More in a later blog including Saint Eustache and "Madam Mutter".

It was the year that Albert Camus was given the Nobel Prize in literature and his

picture was on the front page of all the newspapers. Uschi and I loved him.

Both his writings and his looks. The young boys outside Alliance Francaise were

not competition at all. Today we would say that he was cool. Camus had been a

member of the resistance during the war, he was born in Algiers and he wrote

similarly to Kafka, as Madame informed me when we got around to Albert Camus in

her education - of me! I was so lucky.

Both Uschi and I still suffered nightmares on account

of the war – we were so young during the war, however, the things I had been

through paled considerably when compared to Uschi and her mother’s flight from

the Russians. We talked a lot about that. Perhaps that was why Camus’ texts

made such an impression on us. The symbolism of The Plague sent shivers down my spine: fascism, the persecution of

the Jews along with everything else.

//As Rieux stood

listening to the cheering city,

he remembered that this expression of jubilation was constantly at risk, because he knew what the exultant crowd of people did not, even if you could read about it in books, namely that the germ of the plague never dies and never disappears completely; it can slumber for decades in furniture and linen; patiently biding its time in living rooms, basements, suitcases, handkerchiefs and old papers, and then the day may arise, when you least expect it, and the plague will once again awaken its rats and send them off to die in a happy city.//

he remembered that this expression of jubilation was constantly at risk, because he knew what the exultant crowd of people did not, even if you could read about it in books, namely that the germ of the plague never dies and never disappears completely; it can slumber for decades in furniture and linen; patiently biding its time in living rooms, basements, suitcases, handkerchiefs and old papers, and then the day may arise, when you least expect it, and the plague will once again awaken its rats and send them off to die in a happy city.//

Algiers gained its independence in 1962, but by that

time, Uschi and I had both long since returned home. We wrote to one another

until the Berlin Wall put a stop to that. Or at least I no longer received

replies to my letters.

However, we were still in Paris:

Walking home together at night did not prevent a

mugging on our way back from Champs Élysées and a trip to the cinema or a

frightening experience in Louvciennes, a small town approx. 11 miles outside of

Paris, where I spent the following summer on my own with the family’s three

children. Madame had given birth to little ‘Corontin’, the much longed for son

during the winter.

I survived ... both children and Arabs, and I’ll get

back to that in another blog.

And although he was offered a position as organist and

composer at Versailles, he would rather break an arm than not follow his dream

and plan: to compose operas! He was finally free of his two tormentors from

Salzburg; papa Leopold and his

employer Prince and Bishop Hieronimus

Colloredo, and he did not want to tie himself down to yet another

aristocrat, let alone the French King.

Mozart did not think that making a living as an

independent composer would pose any problems ... his independent streak was

already in full bloom.

Madame Mutter tried to

persuade her son to accept the position at Versailles, keeping their financial

situation in mind, which Mozart was well aware of. He gladly sold off everything

that he could do without.

Anna Maria fretted, but she had no way of controlling her

freedom-seeking son, even if that was the real purpose of her accompanying him

on this journey.

She would highly likely have argued that there was a

far from insignificant theatre at Versailles, Opéra Royal, where Marie Antoinette would joyfully perform whenever

she felt like it.

When the Queen read Beaumarchais’ play, The

Marriage of Figaro, which Louis XVI had denied all theatres the right to perform, she was so excited that she put on

the play regardless, with herself in one of the leading roles, and it is

claimed that the king enjoyed himself immensely.

Opéra Royal, which was situated within the castle

itself, could seat 1000 spectators and was built quite modestly from wood,

stucco and papier mâché. In 1777 it would have been a revelation.

In 2009, the opera was opened after a complete

renovation and as is visible in the video below, modern audiences could

experience the wild ‘Spectacles’ exactly as the spoilt nobles did hundreds of

years ago. Except for Mozart ... or he would most certainly have mentioned it

in his letters to Papa Leopold. And if he hadn’t, his mother surely would have.

Enjoy!

SPECTACLES À VERSAILLES

Realisateur Monteur: Peterson Almeida:

To be continued in Blog 3

To be continued in Blog 3